As an independent developer, I ‘ve had my fair amount of successes and failures – examples of the former are TVPyx (Symbian, Windows Phone, Web) and TubeBusBike (Symbian).

Having developed apps on iOS, Android, WP, Symbian, Bada and Web – my experiences of all stores has been mixed. As an independent developer it is increasingly difficult to get noticed in the sea of apps that are available on the various stores. I have had a fair amount of trial and error experiences with both advertising and merchandising across those stores. I ‘m here to share my experiences with both.

There are a number of techniques available to developers that can be used to promote your app and increase downloads. Some of these you will need to pay for, some of which are just down to hard work and slick execution. Of course there is always an element of luck and right place right time usually built upon previous failures, think Rovio. I am going to concentrate on two methods of promotion.

Advertising and cross promotion – The method of promoting an app either through paid in-app advertising i.e. in someone else’s app/website or cross promotion through apps developed by the same publisher.

App store promotion – The practice of promoting an app via app stores. Merchandisers (app store owner staffers) select apps by country/region to appear as featured or promoted apps on the store. Various ‘slots’ have different success rates where ‘featured’ is usually the Holy Grail in terms of maximizing eyeballs and downloads.

Advertising

Advertising using one of the mobile ad networks like Admob or an ad exchange like Inneractive is a paid-for activity i.e. you would pay for a campaign of ad impressions to promote your application in the usual advertising model. While someone like Admob may be excellent in a market like the Germany, they may lack in a specific region like Vietnam. This is where an ad exchange comes in. If you have a truly global application or specific regional needs that no one ad network can provide the required local content, an ad exchange barters on your behalf with local inventory and then serves the ad that gives you the most return.

Not all ad mechanisms are created equal, so you should take care whilst selecting one. While the fill rate may be excellent compared to a single network, the downside is that you may not be getting premium content that would be served by a truly local provider i.e. lower CPM. So while a fixed ad network can provide targeted delivery in terms of locale, an ad exchange can level the playing field especially in those maybe hard to reach areas of the globe. You need to understand your market and choose accordingly.

My personal experience of using paid-for app promotion was very disappointing. For £1000 one of my apps was involved in a campaign that consisted of a carousel with 4 ads shown in succession. The campaign as a whole garnered 260,000 impressions. My ad was the 4th on the carousel meaning that it would be the 4th ad served once the app the ad was in was invoked. Quite far down the pecking order. From this campaign there were 82 clicks of which it is unclear whether any of these actually resulted in any downloads. No spike, no step change, just noise. The ad was targeted at UK mainly but a few other countries were involved. So quite a high customer acquisition rate!

Anecdotal evidence suggests that in some markets, advertising in apps might even have an adverse effect on downloads, as they use data which comes at a cost to the user.

App Store Promotion

Being a ‘featured’ app on any store will dramatically increase downloads. Naturally being featured in a store is likely the result of one of the following; it’s a great app, it’s a great experience, great PR, a relationship with a journalist on a national newspaper, major marketing budget, lots of hard work and maybe a bit of luck to name a few.

To get noticed by a store owner – especially an OEM – you need to consider what they as the builder of the devices are currently trying to push. For Nokia it may be imaging or mapping i.e. you are more likely to be promoted if you are harnessing one of the strengths of the business, what makes them unique. For Samsung it may be an app that integrates with their TV solutions. Segmentation considerations also work e.g. apps for a demographic that are being targeted by a particular device or devices. Building a relationship with an app store owner is a means to get promoted but this is likely to be the result of an app that meets the needs of a campaign or some quid quo pro between the developer and the likely OEM. A strong relationship or understanding of needs is required regardless of approach. I am privileged enough to have been involved a number of OEM programmes and have some close relationships with a number of OEM’s and platform providers so this approach has very much worked for me.

There are a number different areas on a store where you can be promoted; featured, staff picks etc. Some OEM’s have mini stores that usually link to their platform stores like Windows Marketplace or Play. This gives the OEM the ability to merchandise their partner apps without seeking the permission of the platform owner. Nokia has the App Highlights app shipped with all their phones, other OEM’s have their own offering.

My experience of being featured on Windows Marketplace was great for downloads as I suspect being featured would be on other stores. App Highlights worked well until Nokia changed the app due to having to try to promote more apps themselves. This meant my app started to get lost in the sheer number of apps being promoted. The latter being the inherent problem of managing app promotion on store.

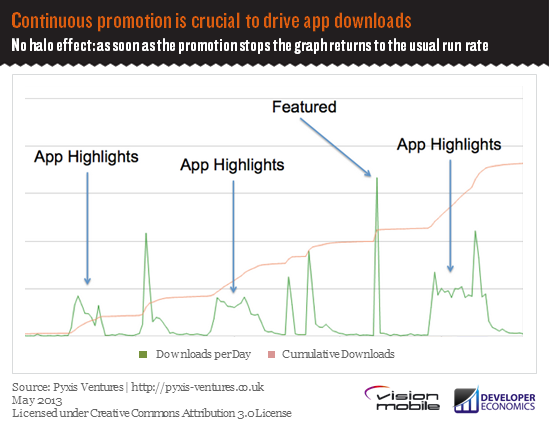

Below is a graph of my own experience of being featured on Windows Marketplace and being promoted through App Highlights. There is no halo effect, as soon as the promotion stops the graph returns to the usual run rate. The implication is that you have to continue to promote and market the app to get downloads. As you can see the experience is far more positive than paid-for app advertising. Being featured represented a 1000% increase (800 downloads/day) in downloads whilst being included in App Highlights represented a 200% (160 downloads/day) increase in downloads.

There are other spikes on the graph that are not either Featured or App Highlights. The honest answer is I don’t know what caused them. I only know that my app was featured or highlighted because a) someone told me or b) I happened to know the right people. The other spikes could have been caused by promotion on other parts of the store that I was unaware of or a blog picked up on the app etc. It is usually the case that the developer is not told that their app is being promoted which seems a shame for the developer and the store owner not to be able to capitalize on the promotion.

Conclusion

To get downloads, you need to continuously promote and market your app. I experienced no halo effect, as soon as the promotion stops the graph returns to the usual run rate. For me, getting featured and highlighted was a far more effective solution than paid-for advertising. The key is to build close relationships with multiple OEM’s and platform providers and use it to deeply understand their marketing needs.