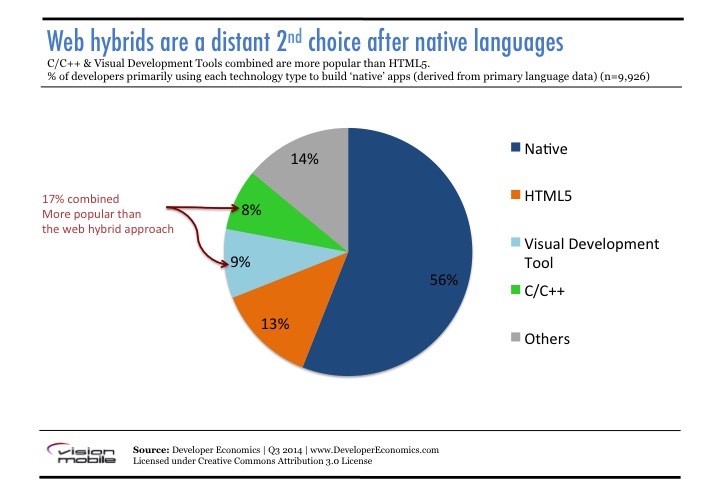

Although building a separate native app per platform is currently proving to be the most successful approach for mass market consumer apps, there are still a lot of situations where it makes more sense to go cross-platform. In this article we’ll look at the most popular option, hybrid web apps built with HTML5, versus an up-and-coming challenger, Qt.

How do you build web apps? Take the Developer Economics Survey and let us know. Cool prizes await you.

Why Qt?

Those who know the history of Qt may be surprised to see it described as “up and coming”. Qt was originally designed for building cross-platform desktop apps, it’s creators started working on it in 1994! However, Qt became interesting for mobile development after Nokia bought Trolltech, the company developing Qt at the time, and invested heavily into making it the ideal toolkit for building mobile apps. Unfortunately, Nokia was making this strategic decision shortly before the iPhone launched (the acquisition was completed afterwards). This changed the game from building apps for devices with numeric keypads and Qwerty keyboards, to large touch-screen based devices. The former Trolltech engineers recognised that they needed a very different way of creating apps for Nokia’s offering to compete.

When Steve Jobs said that the iPhone was 5 years ahead of the competition at launch, he was not far wrong. Android had managed to close some of that gap, probably due to executives at Google having some advanced warning about the iPhone. Unfortunately, Nokia eventually gave up on it’s own Qt based devices in favour of Windows Phone as the software efforts were taking too long and they were falling a long way behind in the ecosystem wars. They sold Qt to one of their major services company suppliers – Digia – who have recently established a fully-owned separate entity for the product, The Qt Company. Only after being fully disentangled from Nokia has Qt been able to return to its roots as a cross-platform framework and start supporting the major mobile platforms. However, in the mean time, others had seen the great foundation for mobile apps that Nokia’s investment created. As a result the BlackBerry 10, Jolla Sailfish, Ubuntu Mobile and Tizen platforms all have Qt as a core framework.

From a personal perspective, I re-wrote a popular iOS game for Symbian using Qt in early 2011. The UI design and general debugging tools were a bit immature at the time but it was one of the simplest learning curves and most pleasant development experiences I’ve had on any platform (note: I was not paid to say that), even though the core of Qt is using the less than developer friendly but high performance C++. I was able to achieve smooth 60fps performance on some rather low-spec hardware. It was easy enough to learn their new UI technology, Qt Quick, and build the menu screens for the game with it in a couple of days.

Why HTML5, or why not?

HTML5 is the most popular option for developers building cross-platform mobile apps, however, it appears to be falling out of favour a little. Web browsers and web views are available on every platform and web developers are able to transfer their skills from building websites to building mobile apps. Open source frameworks like Cordova (PhoneGap) allow developers using HTML5 to access additional mobile specific functionality and make it easy to package apps in a native format for each platform. The added bonus is that you can usually have a version of your app on the web as well as in the app stores for minimal additional effort. HTML5 is generally more productive for building UI centric applications than native apps. There is also an embarrassment of riches when it comes to libraries and frameworks for building mobile web apps. Hybrid web apps are in the privileged position (on iOS at least) of being able to update their code directly, avoiding the App Store review process for all but major changes.

Given its ubiquity and large developer base, why isn’t HTML5 the default cross-platform approach? [tweetable]Despite many advantages, hybrid web app developers have been struggling with performance[/tweetable] (partly due to crippled or outdated webview implementations, an issue which has been fixed in the latest versions of iOS & Android, although this will take a while to penetrate the entire installed base). There is also an issue with varying levels of support for standards across mobile browsers (again, this is something that’s improving but not entirely fixed yet). Web technologies have also not really been designed for the highly animated UIs that are now expected by mobile users. This is something that the much hyped Famo.us framework aims to resolve.

A number of very high profile consumer startups have publicly switched from web hybrid to native mobile app approaches. The most common reason stated for these switches has been lack of adequate tooling. It’s certainly possible to make web apps perform well on mobile devices within their limited memory budgets but with the current state of debugging and profiling tools, that’s still not an easy thing to do compared to producing native apps. This said, not all apps need flawless UI animations and we’re not comparing HTML5 with native, so lets look at how it goes head to head with Qt.

Qt vs. HTML5 – Pros & Cons

Supported platforms:

- HTML5 is supported almost everywhere.

- Qt is supported on all major platforms (and minor ones that happen to use it for their UI).

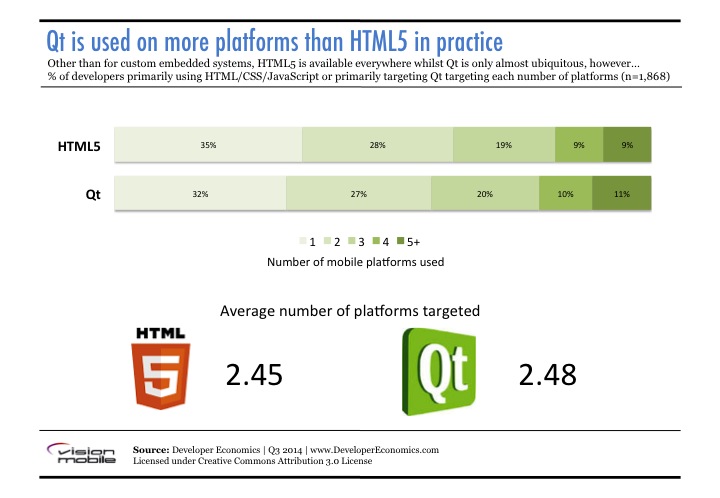

Although in theory you can target more platforms with HTML5, this is not how most developers are using it in the real world. [tweetable]HTML5 developers are increasingly abandoning the browser and building hybrid apps[/tweetable]. Most mobile developers are targeting some subset of Android, iOS, Windows Phone, Windows 8 and BlackBerry 10. Qt supports all of these and more. In fact, in practice our data shows that Qt developers actually target fractionally more platforms on average than HTML5 developers. As a result, this is basically a tie for most developers with a significant advantage to HTML5 for those who really want to run their software everywhere (feature phones, Smart TVs etc.).

Learning curve:

This one depends whether you’re already a web developer. If you are, learning to build mobile web apps is probably easier than learning Qt. However, if you’re new to either then Qt has significant advantages in terms of having one framework to learn rather than 10s of them to choose from before you even start. Qt also has great documentation, which isn’t necessarily true for all web frameworks. In a fair contest, this is a clear win for Qt.

Openness:

- HTML5 is open standards based and there are multiple open source implementations.

- Qt is open source but dual licensed and effectively controlled by a single vendor.

Clearly HTML5 is more open than Qt. This isn’t always an advantage. The process of creating standards and getting multiple vendors to implement them is slow, Qt can be more agile. If you really need something fixed or a new feature added in open source you can do it yourself or pay someone to do it. If you need to support Internet Explorer and there’s an issue with it, you have to work around or wait for Microsoft. Then again, there’s no vendor lock-in with HTML5 and the web isn’t going anywhere. Someone else could buy Qt and take it in a direction that doesn’t align with your goals. Or they could just put the price up beyond your budget. HTML5 has the edge but it’s not a clear win.

Cost:

- Building for HTML5 is free. There are some non-essential paid tools that can help.

- Qt requires a commercial license for most commercial use on mobile.

Qt’s open source licenses are not compatible with distribution on most app stores. Although the iOS port of Qt is developed in open source, you need a commercial license to ship apps in the store. The lowest cost subscription that allows developing mobile apps for the iOS & Android stores with Qt is $25/month. HTML5 wins.

Cross-platform compatibility:

- HTML5 has multiple independent implementations of a standard.

- Qt has one vendor implementing the same runtime on multiple platforms.

Multiple implementations, with several in open source and a large community reporting on and working around compatibility issues makes for a very robust platform. Even so, having a single vendor making sure all platforms behave in the same way is almost always better for compatibility of your app. Qt wins.

Performance:

- HTML5’s DOM was not built for modern mobile apps.

- Qt Quick’s (QML) scene graph is built directly on top of OpenGL ES.

Both environments use JavaScript. However, with Qt it’s much easier to drop down to native code if you really need native platform functionality or performance. The performance penalties for switching between JavaScript and native code are much lower with Qt. The biggest difference however, is graphics performance. People looking for serious graphics performance with HTML5 resort to complex schemes to avoid touching the DOM as much as possible. Building the entire UI on top of WebGL seems like the most promising path to future performance, now that WebGL has much wider support (Apple adding this in iOS8 is key). Qt has a massive advantage here, it also has more extensive animation options than CSS3 for web app developers.

Native user experience:

- With HTML5 you rely on either a 3rd party framework like Ionic or building your own clones of native interface elements.

- With Qt you can use components that clone native interface elements, or use real native UI calls.

Being able to call native APIs in Qt potentially gives it the advantage here but in reality this loses cross-platform compatibility. In practice neither option is really well suited to situations where you need a genuinely native user experience. Both can emulate one adequately for a subset of possible apps. In general it’s best to use a cross-platform approach where a fully custom UI is needed, or a native look and feel is not essential.

Conclusions

Comparing across these metrics, Qt has a slight edge over HTML5. However, there are other metrics you could use that would give the opposite result. In practice the technology needs to be selected to fit the project. Both options have merits and if you’re an HTML5 developer who’s not already familiar with Qt’s offerings, they’re worth a look. I also didn’t mention that Qt apps can display HTML5 content in a webview, meaning that it doesn’t have to be one or the other, it can be both.

Which one do you prefer? Take the Developer Economics Survey and let us know.