If you want to target multiple mobile platforms without having to maintain a separate code base for each one of them, mobile hybrid apps is one way to go. What mobile hybrid apps won’t do, though, is relieve you of the need to manage and use multiple tools, e.g. building your app for a specific mobile platform requires installing the platform’s native SDK on your machine.

ICEs are here to take this headache away. ICE stands for Integrated Cloud Environment and it’s essentially an IDE that does some of its work in the Cloud. A typical ICE for mobile hybrid app development provides you with tools to design, write, test, debug and profile your app. It also allows you to configure the build settings of your app, manage its signing keys and compile it for various platforms.

[tweetable]One of the most popular features of ICEs is building your app in the Cloud[/tweetable] – they grab your code, upload it to the Cloud, build it and come back with the produced app bundle(s). Since the build process no longer takes place on your machine, there is no need for you to install any native SDKs. Apart from building, ICEs may also use the Cloud for storing your app or for pushing it to a device for testing purposes.

A mobile hybrid app development ICE traditionally comes with a companion mobile app that can be downloaded for free from all major app stores. This companion app acts as a container for your own app (your app runs inside it, so you not need to install the former on the device) and also provides some extra functionality (e.g. checking for new builds of your app).

So, here are four of the most popular ICEs for mobile hybrid app development (PhoneGap Build is not really an ICE as we’ll explain later on). But before diving into the details, the following tables provide a handy overview of these tools.

| Tool | Owner | Free? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| AppBuilder | Telerik | No | Desktop-based (Microsoft Windows), Browser-based |

| Intel XDK | Intel Corporation | Yes | Desktop-based (Microsoft Windows, Ubuntu Linux, Apple OS X) |

| Monaca | Asial Corporation | Yes * | Browser-based |

| PhoneGap Build | Adobe | Yes * | Browser-based |

* A free subscription plan is offered (among others).

| AppBuilder | Intel XDK | Monaca | PhoneGap Build | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code editor | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ |

| Drag-and-drop tool(s) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ |

| Source version control | ✔ | ✘ | ✘ | ✔ |

| Collaboration | ✔ | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Device simulator | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | ✘ |

| On-device debugging | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| On-device profiling | ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | ✘ |

| Builds | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Companion app | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ |

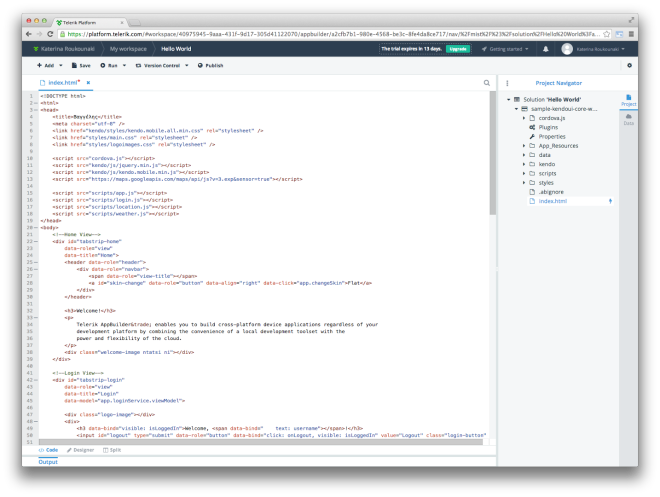

AppBuilder

With AppBuilder (previously known as Icenium) you can develop your app in collaboration with other members of your team, using both a code editor and a drag-and-drop tool (experimental and limited to apps that use Kendo UI).

AppBuilder allows you to test your app on a built-in device simulator, on native emulators installed on your machine, as well as on real devices (both connected and remote). In the case of real devices, you can either install your app or run it inside the AppBuilder companion app.

While your app runs on the simulator or on a connected device, you can debug it using the bundled debugger that’s based on Web Inspector. AppBuilder also allows you to automatically reload your app as you make any changes to its source code.

❢ AppBuilder offers Cloud-based storage and version control for your apps.

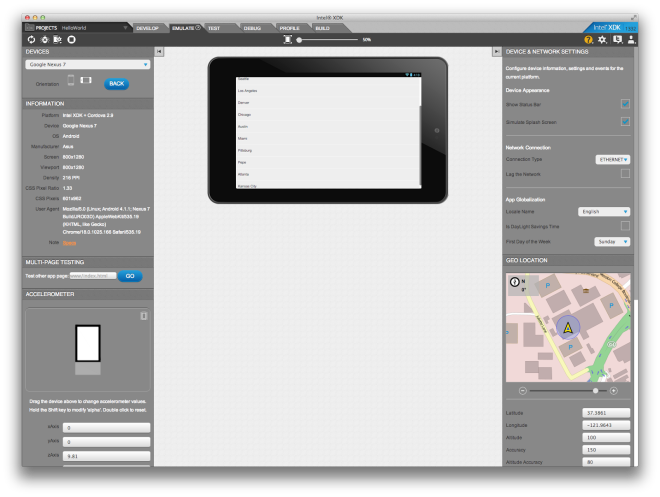

Intel XDK

Intel XDK contains a bundle of tools: a code editor that is based on Brackets, two drag-and-drop tools that help you design your user interface (one supports App Framework, Bootstrap, jQuery Mobile and Topcoat, while the other is limited to App Framework), and a device simulator that is based on Apache Ripple.

In addition, Intel XDK allows you to test your app on real devices that are connected to your machine or are in the same wireless network as your machine. In both cases, you need to have App Preview (Intel XDK’s companion app) installed on your device. Similarly to Telerik’s AppBuilder, Intel XDK automatically reloads your app (if you’re using an Android handset) as soon as you make changes to the source code.

With Intel XDK you can also debug and profile a running app. On the device simulator you can use a debugger that is based on Chrome Developer Tools (CDT). On a real connected Android device (with both App Preview and App Preview Crosswalk installed on it), you can use weinre (WEb INspector REmote) and a built-in profiler that helps you identify hot-spots in your Javascript code.

❢ Intel XDK supports live layout editing. While your app is running on a connected Android or iOS device, you can preview the result of the changes you make to your HTML and CSS files as soon as you hit save.

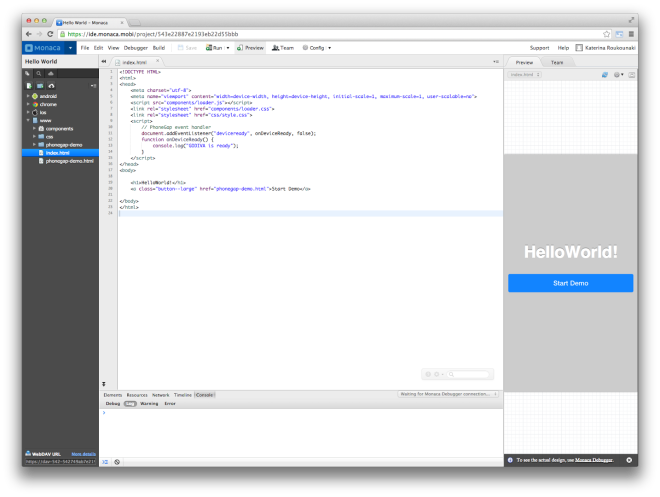

Monaca

Monaca allows you to collaborate with other testers and developers on developing your app. You can chat with them as you write code, and share your thoughts, as well as screenshots of your running app, while debugging it on a real device.

With Monaca, you can preview your app in a browser (with different device screen sizes and orientations) or run it on real devices inside Monaca Debugger (the companion app of Monaca). In both cases your app gets automatically reloaded every time you make changes to the code and save them.

You can debug your application in preview mode, using the debugger that comes with your browser. Alternatively you can debug on a real device, using Monaca Debug Panel, a tool based on Web Inspector. Some debugging features are also available on the real device; for example, you can view the source of the current page or inspect the application log.

❢ Monaca stores your code in the Cloud, and you can access it at any time and from any place using WebDAV.

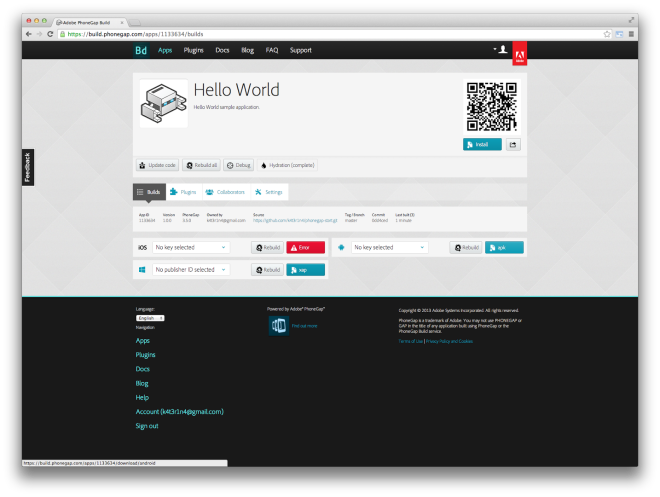

PhoneGap Build

PhoneGap Build is not really an ICE, but rather a build service that works in the Cloud. It pulls the source code of your app from either a .zip file or a (private or public) Git repository, and then allows you select the platforms you want to build your app on. Throughout the building and testing process, PhoneGap Build enables you to collaborate with testers and developers from your team.

PhoneGap Build allows you to build debug-enabled and/or “hydrated” versions of your app. With debug-enabled builds you can remotely debug your app using weinre, whereas new hydrated builds can be automatically pushed to the devices and replace older ones.

❢ PhoneGap Build does not store the passwords for your signing keys for more than one hour since the last time you used them.

To sum up

Mobile hybrid apps allow you to target multiple mobile platforms with less code, in less time, and with fewer programming languages. ICEs for mobile hybrid app development move parts of the development process in the Cloud (e.g. they build your app there), thereby adding one more benefit to the above list: fewer tools.

There are several reasons for trying out an ICE – the choices differ according to what you’re trying to achieve. If you enjoy writing code on the Web, you can use Monaca, while if you want to spend less time on writing code, AppBuilder’s and Intel XDK’s drag-and-drop tools might make your life easier. Keep in mind that using an ICE does not require abandoning your current editor or IDE – you can use any editor or IDE you like and then import your code into an ICE to test, debug or build your project. Finally, there are some cool features in this post that might have caught your eye – e.g. Intel XDK’s remote profiler or Monaca’s collaboration tools. So, get started with an ICE – and let us know what you think!

Update Dec 15, 2014: Monaca kindly informed us they also provide full debugging functionality via USB, using Chrome on Android and Safari on iOS devices.