In a world that is increasingly dominated by mobile applications and cloud services, APIs are becoming crucial to developers and service providers alike. But what are developers actually getting? And is this what service providers think they provide?

Developers

Developers want to use APIs that extend their service without having to either build the technology themselves or comply with required legislation or security (think payments or anything to do with storing large amounts of personal details).

[tweetable]Developers want simple, scalable, well-documented APIs that are as reliable as possible[/tweetable]. They do not want API they use to make their service unreliable, buggy or slow, i.e. make them look bad. Poorly-performing APIs can harm a developer’s reputation but also the API provider’s, should the branding of an API be visible to the world (think Twitter, Facebook, Instagram).

API Providers

API providers grant access to a service or services through the use of public or private APIs; a private API being a service that is not for public consumption for privacy or security reasons. Why grant access at all? To allow developers to use services and functionality that they do not have to build themselves and provide stickiness to an existing user base. Salesforce has done an amazing job of allowing third-party developers to use and extend the functionality that is provided and has even allowed developers to build a thriving apps and plugin community.

API providers look to balance the load on their servers that may also be dealing with other services. They are trying to provide minimum response times whilst maintaining the access and integrity of the data and the service for the developers.

Schrodinger’s API, it both works and doesn’t work at the same time

Here lies the problem; when an app that relies on an API performs badly whose fault is it? Is the app performing how the developer expected or is the API not responding and thus slowing the service? I[tweetable]t is very easy for the API provider to believe that just because the green light is on that the API is working[/tweetable]. Many systems behave completely different from the theoretical under load, when exposed to extreme conditions or elements beyond normal operation or even users doing unexpected things to the API.

Logs

System logs, either from servers, application monitoring tools or other conventional developer operating systems are excellent at hiding things because there is usually a lot of data to digest and identifying the issues from the noise can be nearly impossible.

Some examples include:

Averages – Whilst an average latency of 300ms may look ok its not if you are still getting a number of calls that take 10 seconds. To understand whether or not your slow performaning outliers are an issue means you have to look at the distribution of latencies and the frequency of the outliers.

Errors rates – hopefully these are low. Even a low error rate in a popular API can represent a huge issue. Consider an API that deals with 2 billion transactions a day at 0.2% error rate still has 4 million failed calls a day.

Logs only measure calls – If the API is not frequently used then the logs are not going to tell you anything. If the bulk of transactions are say only done on a Friday but the services failed on a Thursday then the detail will not be in the logs. Only frequent monitoring will notify you of issues before they hit your users.

Basically what the logs don’t tell you is how APIs work end to end, in different geographic regions and what the end-to-end latencies are when using real transactions.

Some simple rules

Monitoring is for life not just for Christmas.

An API that is switched on may not stay on but may be on every time you check.

The reliability of an API is inversely proportional to the number of people using it and the number of developers trying to do things that may break it.

The use of server logs is a function of user base and the amount of data being recorded.

Test the API like it would be used in the wild, end-to-end across a range of cloud services and apps. In this instance cloud services means hosting platforms like Google Apps Engine, Amazon Web Services and Azure to name a few.

Key question to ask is whether the servers are being tested for performance or the API and the impact on users and the overall experience?

As a developer and a user of services it’s the experience that matters. Poor experience equals poor brand perception, which leads to trying a different API or app, losing the client whether it’s a developer or a guy with an iPhone migrating onto the next app.

Things to consider when testing

Where is the data being served and where are your users?

An app that works in San Francisco when the server farm is in Mountain View may show differences when the same server farm has to serve the app in Europe. Test the API from different locations.

I got a HTTP200 response that means everything is fine, right?

Whilst most of us have seen HTTP 404’s, page not found, we also know HTTP 200 indicates an OK response from the server. The challenge comes from when a HTTP 200 means that things are not OK. For example, in order to avoid browser problems, some APIs only return HTTP 200 with an error message which needs to be parsed. Alternatively, the API might be returning invalid content which could cause an App to fail.

API search function comparison

In the above figure it can be seen that the average latency for search using the Facebook and Twitter API is approximately 2 seconds apart with Twitter being the faster and less erratic. Whilst we can only guess at what is happening in the background the reality is Facebook Graph Search appears to be less responsive to anyone using this feature in an app.

Regional server response variation

The above figure shows Facebook Get response across 6 regions globally. It can be seen that Asia and particularly Japan are poor cousins when it comes to regional performance. This behavior has been viewed with other APIs that have been tested in this way.

Caching data

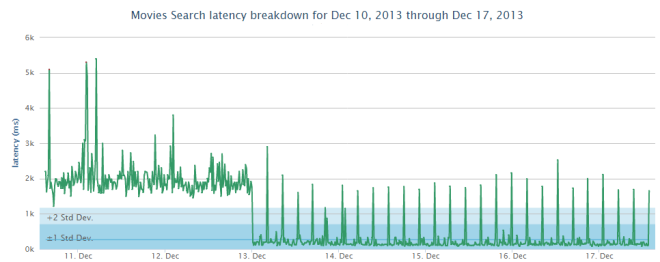

The above figure shows the effect of caching on server response. After caching was implemented on the server it can be seen that response improved, even during refreshes (the spikes) overall performance was up.

Server issues

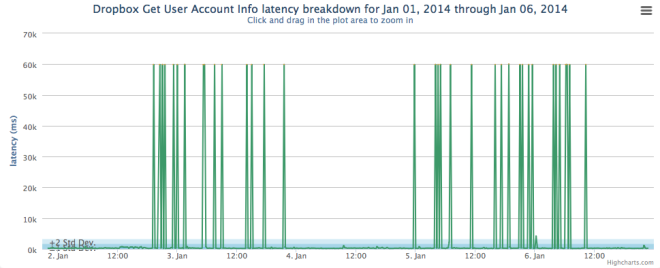

The above figure shows intermittent server issues over time. This can be indicative of load balancing issues or a problem with a server in a server cluster.

What is the future?

[tweetable]The number of APIs is only going to increase and developers are likely to rely on 3rd party services more and more[/tweetable]. It is also likely that more than one API from more than one provider will be used in an app. How can we mitigate against the response of one API compared to another? We see a need for intelligence in the app that can let that user know that something may be awry with the service trying to be accessed. This should be utilized as part of the UI flow to warn that ‘hey looks like is not responding, please bear with us’. This would be enabled by pinging the monitoring service to determine if there are any issues reported or the app being alerted automatically on a fail scenario that is outside pre-determined boundaries.

Intelligence in the monitoring will also lead to better understanding of the results and give a heads up to the API providers when issues occur or when the data is showing that a server is about to fail and allow providers to avoid downtime.

Disclaimer: Data was provided by APImetrics.io who focus on API Performance measurement, testing and analytics. John Cooper is advisory board member at APImetrics