Developers struggling to get noticed on the app stores, or hoping to capitalise on the growth of enterprise messaging, are looking to a new way to reach their users – via a chat interface. The logic of reaching users where they spend the most time seems sound, and that is clearly in messaging apps. Does the typical consumer or business user really want to be taken back to the days of the command line interface though? Is this the next big market, or will it just be a trendy niche? [tweetable]Natural Language Processing (NLP) technology seems to be the key to mass market adoption[/tweetable]. Can that interface scale across thousands or millions of apps, or will it be dominated by a few key players and use cases?

An old idea

[tweetable]Chat bots – apps that communicate via a textual, conversational interface are nothing new[/tweetable]. A convincing conversational computer program has been a goal of artificial intelligence research since Alan Turing proposed his famous test in 1950. As long as there have been chat-rooms, including the bulletin board systems that dominated the Internet before the invention and adoption of the web, there have been chat bots. Even commercial scale and conversational access to internet services are far from recent developments. The SmarterChild bot on AOL Instant Messenger and MSN Messenger (now Windows Live Messenger) had 10 million active users and processed 1 billion messages per day. It provided access to news, weather, sports, a personal assistant, calculator etc.

New scale & changing habits

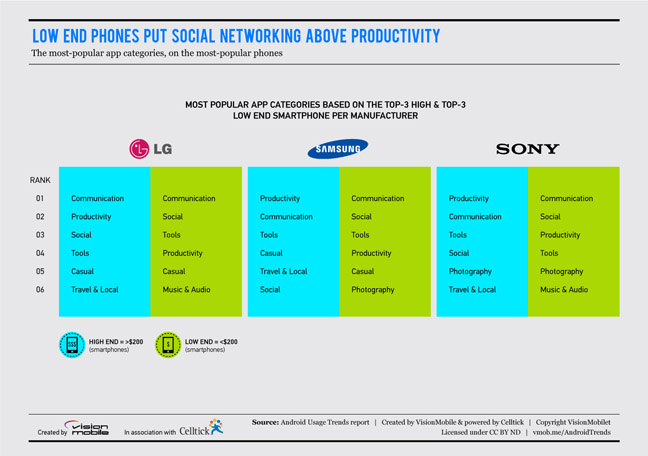

Why the renewed excitement in chat bots? Two reasons – mobile messaging scale and enterprise messaging growth. Third party mobile messaging apps are rapidly heading towards 2 billion active users globally. These apps are typically the most used on any mobile device. Following the model of Asian messaging apps WeChat and LINE, the owners of other messaging apps want to turn them into platforms. At the same time, Slack is attempting to create a platform out of their enterprise messaging product. [tweetable]The impressive growth of Slack in the enterprise, where people are actually happy to pay for software[/tweetable], means a lot of entrepreneurs would like to ride their coattails to success. There are two separate markets here, with a common interface and some common technology.

Better technology for smarter chat bots

It’s the improvement in that common technology, particularly for NLP, that leads many people to think it might be different this time. Conversational interfaces might finally be able to deliver a great experience. However, there are some tradeoffs here for developers. One appealing aspect of a textual interface is that it can be much less effort to develop than a mobile app UI. Unfortunately NLP research has been disproportionately focused on English so far – the technology isn’t as good in other languages, so these interfaces automatically have a more limited audience. The more sophisticated the NLP, the more work involved in developing the interface. Using a 3rd party NLP service can significantly reduce this effort but also removes a key source of differentiation if your product is only a chat bot. Without NLP a bot is either focused on a very specific task or only for power users – mass market consumers aren’t going to want to memorise a lot of specific command syntax. At the other end of the NLP sophistication spectrum, is it going to be viable trying to compete with the likes of Google and Facebook as the best way to access mass market services?

Will Facebook own the consumer market?

Telegram’s bot platform might seem interesting as it reduces the need for NLP (and typing) with dynamic custom keyboards but their reach is a tiny fraction of the likes of Facebook Messenger or WhatsApp. Unfortunately [tweetable]Facebook doesn’t have a good record as a developer platform provider[/tweetable], which they managed to prove again recently, if such a reminder were needed, by announcing they’re shutting down Parse after promising developers their backends were in safe hands. Indeed chat bots on the big consumer messaging platforms may have some success at first but it’s likely to be the platform owners that take the lion’s share of the revenue in the end. These platforms will probably be great for businesses to reduce marketing and customer support costs with chat bots and they’ll be paying Facebook (and possibly others) for the privilege of talking to their customers in this way. There are probably also good opportunities for smaller developers to help companies build these bots.

An opportunity to differentiate enterprise services

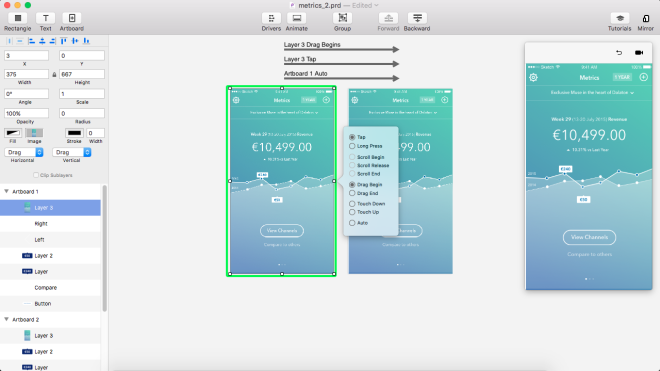

The enterprise opportunity is different. As a growing number of companies reduce their email usage and build workflows around chat in apps like Slack and HipChat, the most natural way to access some premium services will be through chat (at least for some use cases). For example, when discussing past sales, or future sales projections, it would be much more natural to ask an accounting, or forecasting SaaS tool to give you a chart for the relevant period than to switch away to another application to look that up. However, as with most of the obvious examples you could imagine, it’s unlikely that these services would operate entirely through a chat interface. It doesn’t make much sense to enter all of your accounting data via chat or build your sales forecasting model that way. As such, chat bots become just one of many interfaces to a cloud service. There are opportunities for new services to get discovered, or existing services to gain market share, by being early to support chat interfaces but 100% chat-based is unlikely to be a giant new market.

Evolution not revolution

In most cases, consumer or enterprise, conversational interfaces are just another channel. Much like mobile apps are just another channel for many services. They can be a channel that increases convenience or reduces friction for some key use cases. This also follows mobile but their increased convenience and usability lead to a massive increase in total use. The change messaging platforms will bring is nowhere near the same scale as the shift to mobile. The things that were really interesting on mobile were the ones that couldn’t be done, or were too inconvenient to bother with on desktop platforms. What new possibilities do conversational interfaces bring on mobile platforms? What mass market use cases haven’t already been tried (and widely under-used) by Apple with Siri? The most interesting areas are probably those that involve some element of discovery – when you don’t know which app to go to – or embrace the asynchronous nature of messaging. That said, how do you discover a new chat bot to help if you don’t know what you’re looking for? What business models would work for a purely conversational interface? The chat bots may be on the rise, but it’s likely this is more of an evolutionary step than a revolutionary one.