The rise of freemium games has been ferociously quick and it continues to accelerate at an incredible pace. It’s estimated that adults now spend, on average, 5 hours and 46 minutes online and on their mobile devices. Time spent online has now surpassed time spend watching TV.

With more consumers than ever playing games on their mobile devices, developers have had to “evolve” to find the most efficient ways to monetise their potential customers and, from a revenue perspective, [tweetable]the ‘freemium’ model has almost completely killed ‘paid-for’ games[/tweetable].

Putting morals and ethics aside, the freemium route is absolutely genius. Freemium, especially on mobile, can generate vast amounts of profit for developers who manage to create popular applications.

When we ask the question, “are freemium apps killing game developers?”, it always generates an interesting debate. Let’s understand why.

What are freemium apps?

The term freemium can be defined as:

“A business model that provides a game to players free of charge, but charges a premium fee for special features, powers, or content.”

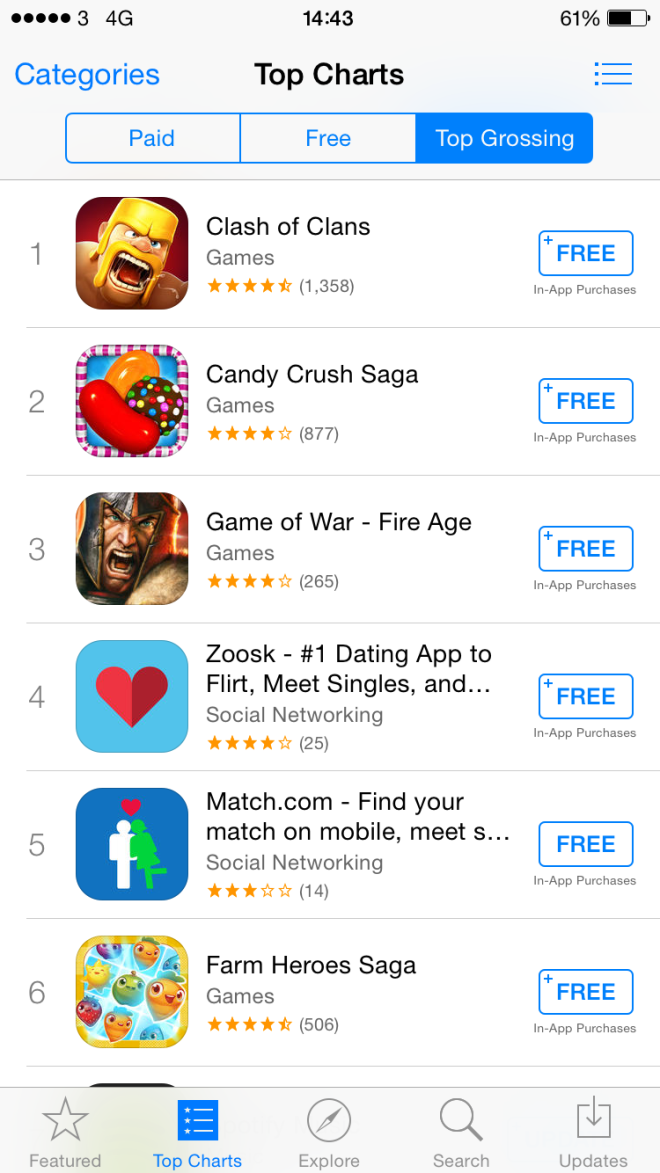

Take a look at the App Store whilst reading this post and you will see the overwhelming majority of top grossing applications are free to download.

To developers, these applications would be classed as “freemium” apps, but the majority of users who download these type of applications believe the developer is making it as difficult as possible to progress within the application in order for you to purchase ‘upgrades’, ‘coins’ or ‘power-ups’ that allow you to progress within the application.

Freemium applications started as an experiment, but very quickly became mainstream. In fact, it was reported last year that 76% of all iPhone app revenue came from in-app purchases.

From a developer’s perspective, freemium games are the preferred route. It’s where the majority of download volume exists and the highest earning revenue streams can be found. Most importantly, their prospective customers’ mindset has shifted. If you are not a ‘free’ game or application, you will have a much harder time selling yourself.

When you speak to independent game developers, they will tell you that more and more revenue could be generated from a free-to-download application. Take an example of a subscription-based game which might charge $20 a month to play. Only a few people might ever be willing to spend that – but far more would be willing to spend 10% of that on a freemium type game. The reality is, when you look at the metrics, there is little to no comparison. Free apps with in-app purchases are potentially much more lucrative.

On the other hand, there may be customers who, even if they were spending $20 a month on a game, would be willing to spend even more if they had the opportunity to. Legacy games never offered that type of flexibility, but things have changed and the top games developers are reaping the rewards.

The thought of ‘what if?’ really did start a new line of thinking. A line of thinking that eventually took the freemium model mainstream.

Why is Freemium seen as bad?

When you look at games from a hardcore gamers point of view, with the above scenarios in mind, you soon realise that the freemium trend is a real negative for them and their style of playing.

[tweetable]The core underlying aspect of freemium games is that you have to pay to continue playing[/tweetable]. Rather than pay a one off fee for a game which would take even the most dedicated gamer a while to complete, there are now deliberate parts of a game or application that force you to spend money in order to overcome a problem.

Roadblocks deliberately placed by a developer force a gamer to spend if they want to continue progressing. It’s this understanding, which has led to many negative reviews of freemium games and the mobile gaming industry in general.

When it comes to developing, freemium games are, arguably, easier for much larger game publishers to make, because these types of games require much more iteration than a traditional paid-for game might demand.

This means that the true independents have a higher barrier to entry than they did before. People expect a lot for free, and if you are not monitoring your audience with a deep level of detail, it’s very difficult to understand when the best time to monetise might be.

Example of the freemium model

Examples of the freemium model taking place inside a game can be found in many different scenarios:

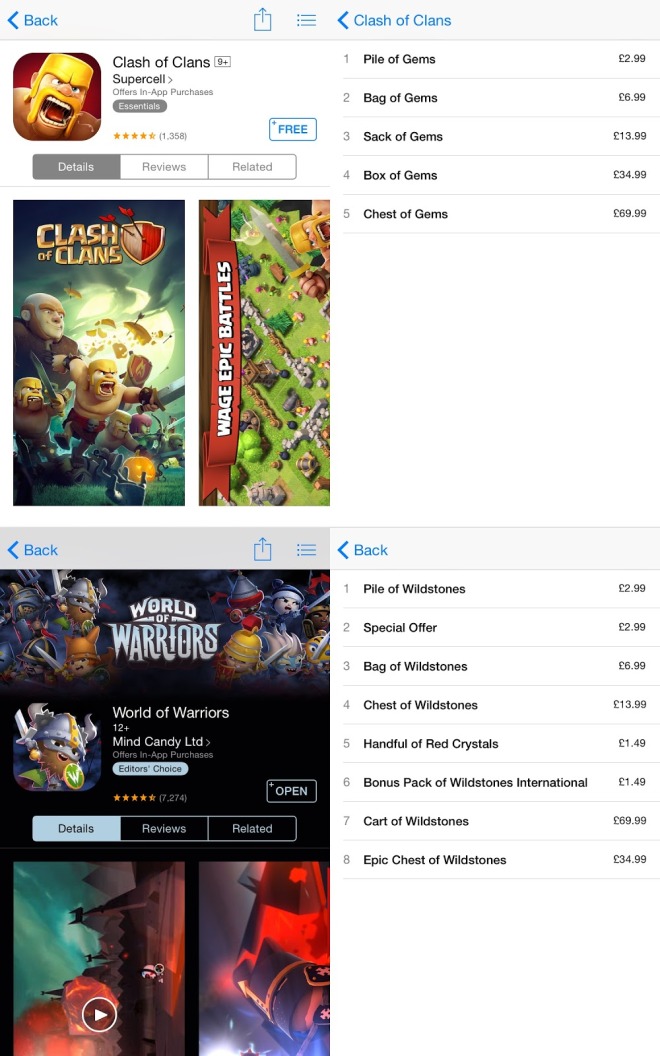

Energy bars are everywhere. The new ‘World of Warriors’ game and ‘Clash of Clans’ from Supercell are good examples of energy meters. In both games, you have ‘food’ and various other ‘elixirs’ which are essentially energy meters. If you have ‘0’ food, you can’t play until it recharges. Regardless of what shape these roadblocks come in, they all serve an identical function: to slow down a player’s progress.

Mobile games would also appear to be getting easier and easier. The majority of these games would not work if a gamer could engage with them and play them for an hour at a time.

Energy meters and time constraints mean that you can only really play an app in small chunks. Unless you pay.

Naturally, a percentage of all users don’t want to wait for their timers to be refilled, so they will pay to get passed what was intended to be a roadblock.

In older, more traditional games, if the player was stuck at a specific part of the game, they would work hard to try and find a solution to the problem they face. However, now if you run into a problem, no matter the quality of the gamer, to get past what might once have been a complex problem – you can pay.

Another very common freemium model is charging for virtual items.

It’s difficult for game developers to understand what is a fair price to charge for various virtual items, but developers are now moving towards simpler monetisation tactics. For example, skipping a level or buying a considerable item which gets them past what was supposed to be a difficult level.

The problem with this is that items like ‘level skipping’ could be free, because it doesn’t actually cost the developer anything to offer hints.

If you compare this with a game we all know, Call Of Duty, giving a player the opportunity to buy new weapons or customise a character has cost the game developer/designer time and money.

Are freemium games killing developers?

Whilst consumers have obviously voted with their wallets that freemium games and applications are what they want to buy, some of us at Tapdaq believe that this has squeezed independent developers into a corner they might not necessarily have wanted to end up in.

There is no doubt about it, I think it’s harder to devote time into creating a game which is long and complex simply because of the natural shift to more casual gaming.

As with all markets, there are two sides to it. In this particular market, you have developers and you have players. If game players are so anti freemium games, then they need to do their bit. They need to start spending money on items which actually cost the developer resources to make, as opposed to buying hints and level-skipping upgrades which defeat the object of playing the game in the first place. They need to value the mobile gaming experience.

New freemium games come out every week in today’s quickly evolving mobile gaming market. This is a business model that, for the foreseeable future, will impact the games we all play. Therefore, game players need to go out and support games that are fair as well as fun to play. Players passionate about game sustainability must vote with their wallets as well as their words.

Looking at the graph below, freemium is proving to be great for developers, but it might have adverse effects, and who knows when we might start to see diminishing returns.

Freemium still has a large share of the market, but it’s unlikely to make you rich.

Freemium still has a large share of the market, but it’s unlikely to make you rich.

I think we’ll continue to see larger game developers dominate the top grossing in various app stores for the foreseeable future, and I don’t think freemium as a business model for games gives a fair platform for genuine independent studios to thrive. However, individuals and small studios who create games are usually far more dynamic and should adapt to evolution faster than larger corporations.

So, is freemium killing developers? The answer is, we can’t be sure yet. One thing is certain, though,the industry will continue to be driven by its customers and customer perceptions of “free” games. Recent events have shown that there is a split between those who are happy to pay for games and additional content within them, and those who expect the game or updates to be free.

A winner for preferred business model has not yet emerged on the mobile platforms, and it is very possible that mobile gaming will evolve in a similar vein to its desktop/console brethren – with games adopting different monetisation methods based on their audience, content and personal preferences.

Let me know what you think in the comments below.