Our 8th Developer Economics survey has once again achieved an industry-leading scale, including responses from more than 8,000 app developers and 143 countries. Their collective insight shows us an app economy that’s beginning to mature. Platform mindshare and priorities are fairly stable and developers are increasingly turning to cross-platform technologies to deal with the multi-platform reality. Tool adoption is gradually increasing and a shift in focus towards enterprise app development is underway. You can get a copy of the full report here – it’s a free download.

The big changes on their way are in development languages and the Internet of Things. Apple’s new Swift has had an impressive level of uptake but C# and JavaScript are also growing in importance. Meanwhile mobile developers are showing a very strong interest in the next wave of connected devices.

Platform Wars

The platform wars have ended in a stalemate. [tweetable]Apple have an increasing lock on the high-end with iOS and Android dominates everywhere else[/tweetable]. Windows Phone is still growing, now at 30% mindshare, but not generating enough sales to break through the app-gap. The split of developer platform priorities amongst full time professionals best illustrates the stalemate. Android has 40% of developers, iOS has 37%, whilst Windows Phone and the mobile browser have just 8% and 7% respectively.

Although not yet a priority the mobile browser has also bounced back strongly from an all-time low in terms of mindshare 6 months ago, with 25% of developers now supporting it. With the massive growth of mobile apps it’s important to remember that the desktop and mobile web combined is still the most important digital channel for the majority of businesses. [tweetable]The web is definitely not dead[/tweetable].

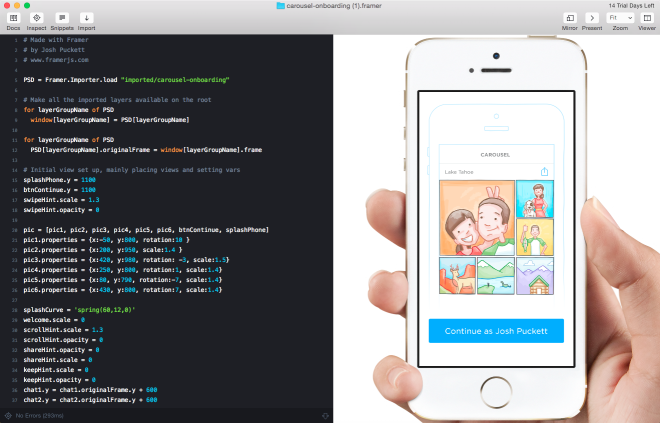

The Rise of Swift

Our development language rankings show absolutely unprecedented growth for Apple’s new Swift language. [tweetable]20% of mobile developers were using Swift just 4 months after it was introduced[/tweetable] to the world. For comparison, Google’s excellent Go language doesn’t make it onto our new top chart for server-side programming languages, having reached just 5% mindshare amongst mobile developers after more than 5 years. [tweetable]Amongst the first wave of Swift adopters, 23% were not using Objective C[/tweetable], a sign that Swift may succeed in attracting a much wider range of developers to build native iOS apps.

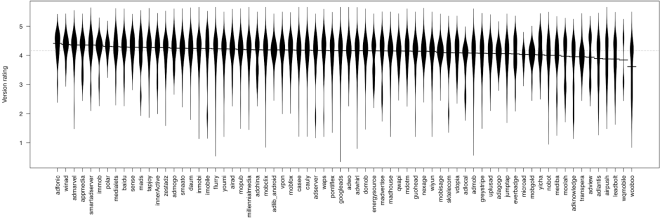

Revenues

Growth in direct revenues from the app stores is slowing. As these direct revenues are preferred sources of income for the Hobbyists, Explorers and Hunters that make up around 60% of the mobile developer population, competition for them is becoming more intense. 17% of developers who are interested in making money generate no revenue related to apps at all. A further 18% of developers make less than $100 per month and the next 17%, bringing us to a total of 52%, make less than $1000 per month.

Those low revenue earners are not at all evenly distributed across platforms. Of those that prioritise iOS, only 37% are below the app poverty line, making less than $500 per month on iOS. On the opposite end of the revenue scale, 39% make more than $5,000 per month on the iOS platform. Rather surprisingly, the revenue distribution for Android-first developers is not much different than for those targeting BlackBerry 10 or Windows Phone. In fact, developers that go iOS first actually earn much more revenue on Android than those that prioritise the platform.

Internet of Things

Despite the relative immaturity of IoT platforms, mobile developer interest is high. A massive [tweetable]53% of mobile developers in our survey were already working on some kind of IoT project[/tweetable]. Smart Home was the most popular market with 37% of mobile developers working on IoT projects targeting it. Wearables were a close second with 35% mindshare. The majority of these mobile developers involved in IoT development are doing it as a hobby (30% involved at this level) or side project (just under 20%), whilst working on mobile apps in their day job. This is expected at this stage of the market where revenue opportunities are still limited.

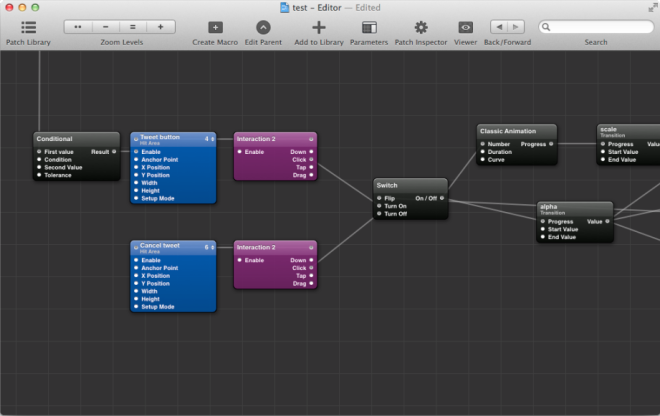

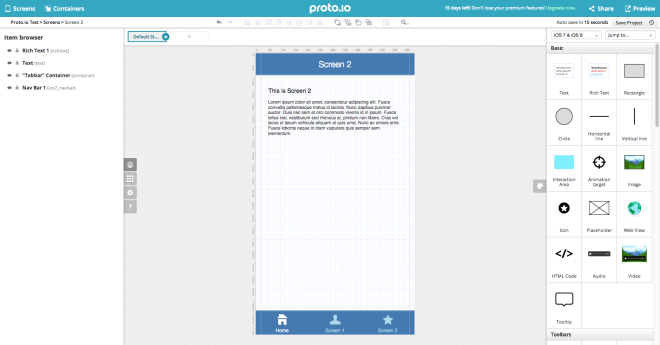

Tools

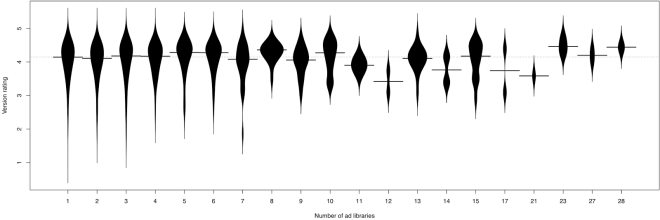

Tool awareness is increasing. The fraction of developers not using any third party tools at all has fallen to an all time low of 17%. The second most popular category of tool is ad networks, with a 31% adoption rate. Unfortunately this is the one category of tool that’s negatively correlated with revenues. Cross-platform tool adoption is on the rise. The percentage of developers using these tools has grown from 23% to 30% over the last 6 months. While cross-platform tool use was previously uncorrelated with revenue it’s now a positive revenue indicator. We don’t believe this is due to a significant improvement in the tools, rather it’s because of their disproportionate use in enterprise app development.

Enterprise vs. Consumer

The enterprise app gold rush is now well underway with 20% of developers primarily targeting enterprises, up from 16% in Q3 2014. This shift in focus is paying off. [tweetable]43% of enterprise app developers make more than $10K per month[/tweetable] versus 19% of consumer app developers reaching the same revenue level.

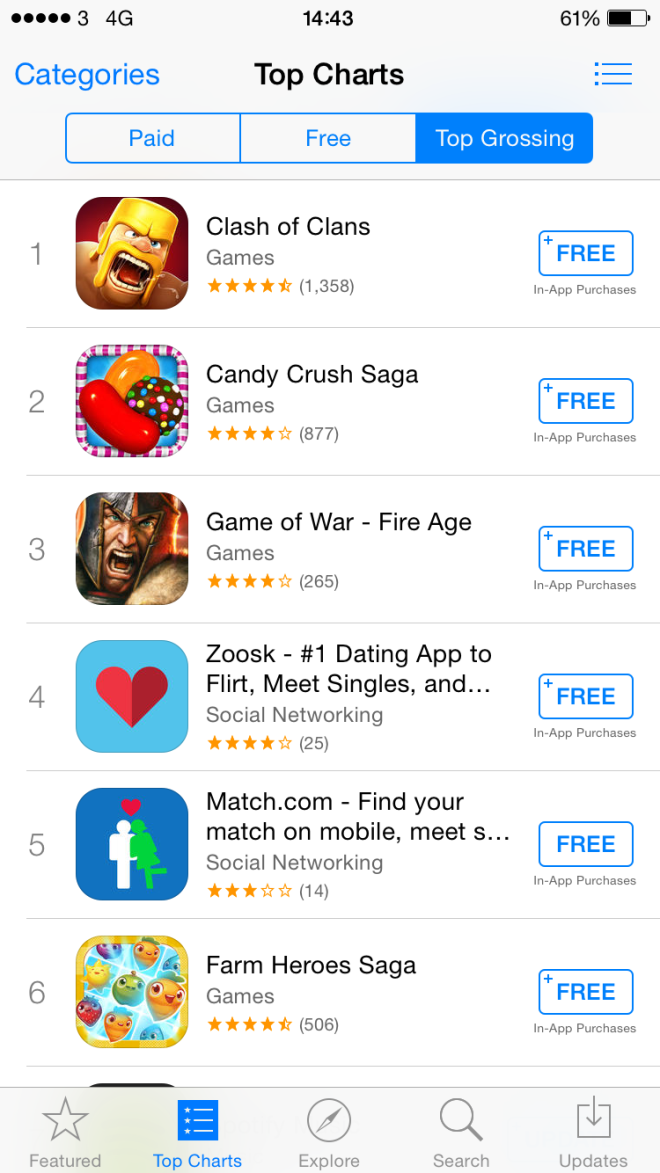

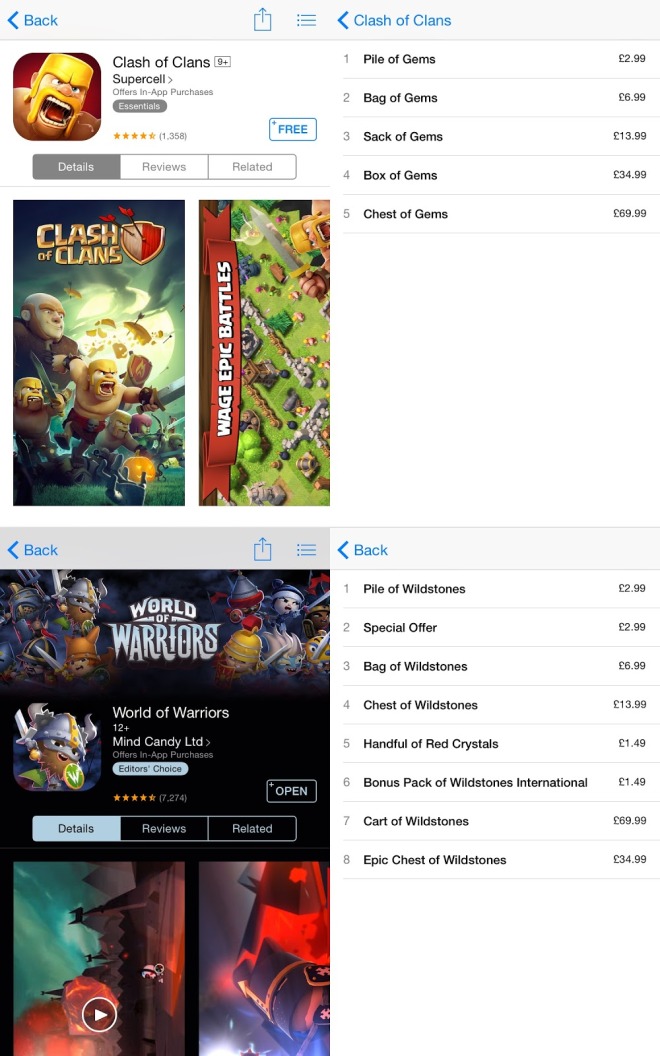

Amongst consumer app businesses, the majority of the revenue is coming from free-to-play games. A typical game is giving a third of gross revenue to the app store provider as a cut of in-app purchases and spending half of what’s left on ads to acquire new users. These game developers are starting to look more like typical fast moving consumer goods businesses, with significant benefits from scale. Despite overall revenues from the stores still rising, life is getting much harder for the small independent developers that try to serve consumers.

The good news for consumer app developers is that 3 of their top 5 favourite categories are common with enterprise app developers. It’s definitely not too late to re-focus on B2B rather than B2C sales. Also, the skills developed building consumer apps are in greater demand than ever now that more and more businesses are taking mobility seriously. This is a trend that will keep running for several years yet.

Want more? Download and read the full report!

Freemium still has a large share of the market, but it’s unlikely to make you rich.

Freemium still has a large share of the market, but it’s unlikely to make you rich.